On an unassuming morning off the Norwegian coast, millions of small fish called capelin began to gather in the ocean. Soon enough, they amassed to 23 million individuals, forming a group over 6 miles long.

Nearby predators, Atlantic cod, took notice.

Over just a few hours, marine researchers, using a sonar imaging system, observed a colossal congregation of cod consume over 10 million capelin. It was the largest predation event ever documented in the ocean.

“It’s the first time seeing predator-prey interaction on a huge scale, and it’s a coherent battle of survival,” Nicholas Makris, a professor of mechanical and ocean engineering at MIT and one of the study’s authors, said in an MIT statement.

This research from the Barents Sea was published in the peer-reviewed science journal Nature Communications Biology. The observations are from February 2014, but new techniques have illuminated the predation event by allowing scientists to clearly differentiate the cod from the capelin.

To our species, the event appears extraordinary or violent. But nature is commonly ruthless. In the dark deep sea, home to sprawling groups of animals, such natural happenings certainly impact a certain population, but don’t necessarily spell doom for the greater species, like the capelin. The 2014 fish gathering, called a shoal, makes up just 0.1 percent of capelin in this ocean region.

“In our work we are seeing that natural catastrophic predation events can change the local predator prey balance in a matter of hours,” Makris explained. “That’s not an issue for a healthy population with many spatially distributed population centers or ecological hotspots.”

Yet, crucially, as marine ecosystems are threatened and the oceans warm relentlessly, not all populations will always be able to absorb such momentous losses.

“It’s been shown time and again that, when a population is on the verge of collapse, you will have that one last shoal. And when that last big, dense group is gone, there’s a collapse,” Makris noted. “So you’ve got to know what’s there before it’s gone, because the pressures are not in their favor.”

“It’s a coherent battle of survival”

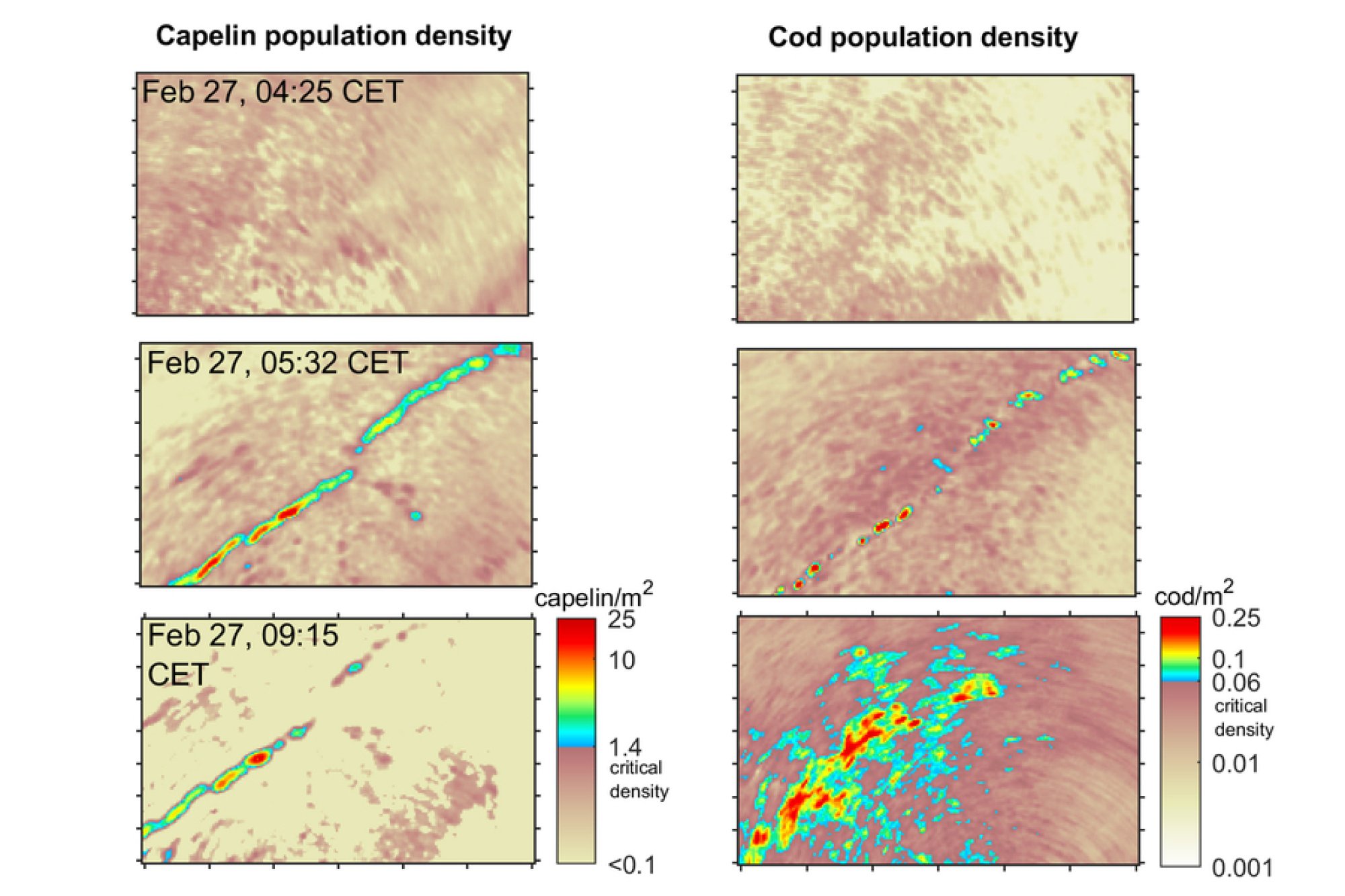

Marine researchers couldn’t be underwater to observe such an expansive, rapidly evolving predation event. But they used an acoustic instrument attached to the bottom of their vessel to beam sound waves into the water below. These acoustic signals, which are commonly used in ocean exploration and mapping, bounce off objects like fish, revealing what’s down there. This specific instrument, called the Ocean Acoustic Waveguide Remote Sensing (OAWRS) system, captured the imagery below.

Importantly, the acoustic signals pinging off each type of fish are distinct, allowing the marine researchers to see both the congregation and predation event.

“Fish have swim bladders that resonate like bells,” Makris said. “Cod have large swim bladders that have a low resonance, like a Big Ben bell, whereas capelin have tiny swim bladders that resonate like the highest notes on a piano.”

Here’s what you’re seeing below:

– Row (i): Both species are seen spread out and randomly moving about the Barents Sea.

– Row (ii): In the early morning, both species create miles-long dense shoals.

– Row (iii): On left (a) is the surviving prey capelin; on right is the “vast engulfing cod shoal,” the researchers wrote.

Credit: Courtesy of the researchers / MIT

Credit: Craig F. Walker / The Boston Globe via Getty Images

Scientists estimate that the larger cod rapidly consumed over half of this giant capelin shoal, numbered at 23 million. Why might the capelin have formed such a massive, conspicuous group? Biologists suggest it allows the migrating animals to save energy as they cruise on the motion created by millions of traveling fish.

And in doing so, they attracted some 2.5 million Atlantic cod — a species commonly eaten by humans.

Such happenings below the surface are often unseen to us, but with these modern expeditions, it’s growing evermore clear that Earth‘s seas are profoundly biodiverse and active.

0 Comments